Según una encuesta de la revista Sight and Sound a la crítica internacional (con mis disidencias expresadas en notas al pie)

THE TOP 50

1. Vertigo

Alfred Hitchcock, 1958 (191 votes)

Hitchcock’s supreme and most mysterious piece (as cinema and as an emblem of the art). Paranoia and obsession have never looked better—Marco Müller

After half a century of monopolising the top spot, Citizen Kane was beginning to look smugly inviolable. Call it Schadenfreude, but let’s rejoice that this now conventional and ritualised symbol of ‘the greatest’ has finally been taken down a peg. The accession of Vertigo is hardly in the nature of a coup d’état. Tying for 11th place in 1972, Hitchcock’s masterpiece steadily inched up the poll over the next three decades, and by 2002 was clearly the heir apparent. Still, even ardent Wellesians should feel gratified at the modest revolution – if only for the proof that film canons (and the versions of history they legitimate) are not completely fossilised.

There may be no larger significance in the bare fact that a couple of films made in California 17 years apart have traded numerical rankings on a whimsically impressionistic list. Yet the human urge to interpret chance phenomena will not be denied, and Vertigo is a crafty, duplicitous machine for spinning meaning…—Peter Matthews’ opening to his new essay on Vertigo in our September issue

2. Citizen Kane

Orson Welles, 1941 (157 votes)

Kane and Vertigo don’t top the chart by divine right. But those two films are just still the best at doing what great cinema ought to do: extending the everyday into the visionary—Nigel Andrews

In the last decade I’ve watched this first feature many times, and each time, it reveals new treasures. Clearly, no single film is the greatest ever made. But if there were one, for me Kane would now be the strongest contender, bar none—Geoff Andrew

All celluloid life is present in Citizen Kane; seeing it for the first or umpteenth time remains a revelation—Trevor Johnston

3. Tokyo Story

Ozu Yasujiro, 1953 (107 votes)

Ozu used to liken himself to a “tofu-maker”, in reference to the way his films – at least the post-war ones – were all variations on a small number of themes. So why is it Tokyo Story that is acclaimed by most as his masterpiece? DVD releases have made available such prewar films as I Was Born, But…, and yet the Ozu vote has not been split, and Tokyo Story has actually climbed two places since 2002. It may simply be that in Tokyo Story this most Japanese tofu-maker refined his art to the point of perfection, and crafted a truly universal film about family, time and loss—James Bell

4. La Règle du jeu

Jean Renoir, 1939 (100 votes)

Only Renoir has managed to express on film the most elevated notion of naturalism, examining this world from a perspective that is dark, cruel but objective, before going on to achieve the serenity of the work of his old age. With him, one has no qualms about using superlatives: La Règle du jeu is quite simply the greatest French film by the greatest of French directors—Olivier Père

5. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

FW Murnau, 1927 (93 votes)

When F.W. Murnau left Germany for America in 1926, did cinema foresee what was coming? Did it sense that change was around the corner – that now was the time to fill up on fantasy, delirium and spectacle before talking actors wrenched the artform closer to reality? Many things make this film more than just a morality tale about temptation and lust, a fable about a young husband so crazy with desire for a city girl that he contemplates drowning his wife, an elemental but sweet story of a husband and wife rediscovering their love for each other. Sunrise was an example – perhaps never again repeated on the same scale – of unfettered imagination and the clout of the studio system working together rather than at cross purposes—Isabel Stevens

6. 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick, 1968 (90 votes)

2001: A Space Odyssey is a stand-along monument, a great visionary leap, unsurpassed in its vision of man and the universe. It was a statement that came at a time which now looks something like the peak of humanity’s technological optimism—Roger Ebert

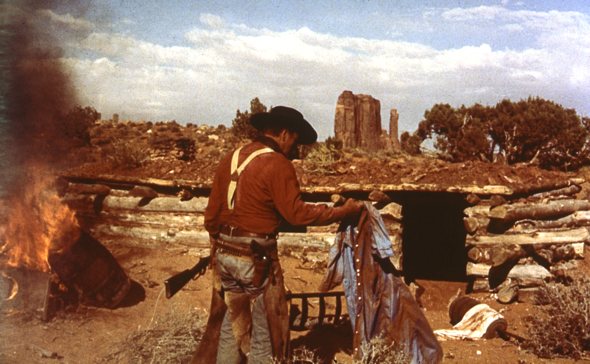

7. The Searchers

John Ford, 1956 (78 votes)

Do the fluctuations in popularity of John Ford’s intimate revenge epic – no appearance in either critics’ or directors’ top tens in 2002, but fifth in the 1992 critics’ poll – reflect the shifts in popularity of the western? It could be a case of this being a western for people who don’t much care for them, but I suspect it’s more to do with John Ford’s stock having risen higher than ever this past decade and the citing of his influence in the unlikeliest of places in recent cinema—Kieron Corless

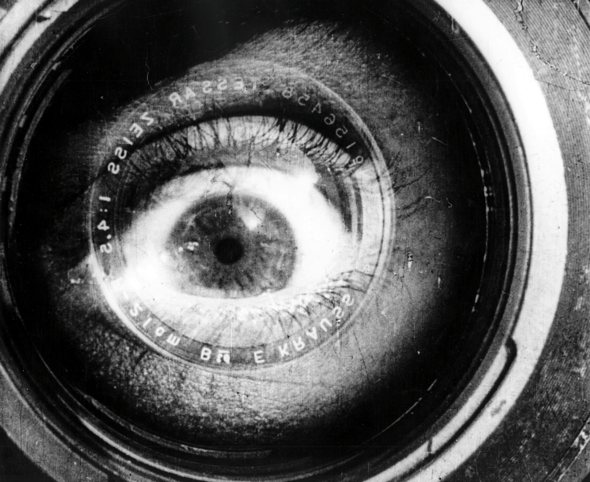

8. Man with a Movie Camera

Dziga Vertov, 1929 (68 votes)

Is Dziga Vertov’s cine-city symphony a film whose time has finally come? Ranked only no. 27 in our last critics’ poll, it now displaces Eisenstein’s erstwhile perennial Battleship Potemkin as the Constructivist Soviet silent of choice. Like Eisenstein’s warhorse, it’s an agit-experiment that sees montage as the means to a revolutionary consciousness; but rather than proceeding through fable and illusion, it’s explicitly engaged both with recording the modern urban everyday (which makes it the top documentary in our poll) and with its representation back to its participant-subjects (thus the top meta-movie)—Nick Bradshaw

9. The Passion of Joan of Arc

Carl Dreyer, 1927 (65 votes)

Joan was and remains an unassailable giant of early cinema, a transcendental film comprising tears, fire and madness that relies on extreme close-ups of the human face. Over the years it has often been a difficult film to see, but even during its lost years Joan has remained embedded in the critical consciousness, thanks to the strength of its early reception, the striking stills that appeared in film books, its presence in Godard’s Vivre sa vie and recently a series of unforgettable live screenings. In 2010 it was designated the most influential film of all time in the Toronto International Film Festival’s ‘Essential 100’ list, where Jonathan Rosenbaum described it as “the pinnacle of silent cinema – and perhaps of the cinema itself”—Jane Giles

10. 8½

Federico Fellini, 1963 (64 votes)

Arguably the film that most accurately captures the agonies of creativity and the circus that surrounds filmmaking, equal parts narcissistic, self-deprecating, bitter, nostalgic, warm, critical and funny. Dreams, nightmares, reality and memories coexist within the same time-frame; the viewer sees Guido’s world not as it is, but more ‘realistically’ as he experiences it, inserting the film in a lineage that stretches from the Surrealists to David Lynch

—Mar Diestro Dópido

11. Battleship Potemkin

Sergei Eisenstein, 1925 (63 votes)

12. L’Atalante

Jean Vigo, 1934 (58 votes)

13. Breathless

Jean-Luc Godard, 1960 (57 votes)

14. Apocalypse Now

Francis Ford Coppola, 1979 (53 votes)

15. Late Spring

Ozu Yasujiro, 1949 (50 votes)

16. Au hasard Balthazar

Robert Bresson, 1966 (49 votes)

17= Seven Samurai

Kurosawa Akira, 1954 (48 votes)

17= Persona

Ingmar Bergman, 1966 (48 votes)

19. Mirror

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1974 (47 votes)

20. Singin’ in the Rain

Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly, 1951 (46 votes)

21= L’avventura

Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960 (43 votes)

21= Le Mépris

Jean-Luc Godard, 1963 (43 votes)

21= The Godfather

Francis Ford Coppola, 1972 (43 votes)

24= Ordet

Carl Dreyer, 1955 (42 votes)

24= In the Mood for Love

Wong Kar-Wai, 2000 (42 votes)

26= Rashomon

Kurosawa Akira, 1950 (41 votes)

Notas al pie:

* Inobjetable Vertigo. Si no es la mejor, es una de las 3 mejores de todos los tiempos.

**Es difícil de objetar. Aunque tiene razón Roger Koza en que ni siquiera es la mejor película de Orson (yo prefiero Sed de mal o La dama de Shangai), Citizen Kane es un film inagotable, gozoso, genial en cualquier acepción del término.

*** Tokio Story es una película inmensa, pero quizá Ozu esté de moda y Mizoguchi lo supere.

**** Con Sunrise sí: totalmente de acuerdo.

***** Comienza el disparate: 2001 ni siquiera es una de las 1000 mejores películas de todos los tiempos. Ponerla en el Top Five es una ofensa al cine. ¿Cuándo cederá el inexplicable prestigio de Kubrick?

****** Sé que The Searchers goza de un consenso casi irreestricto. No me sumo a él, Prefiero al Ford de The Quiet Man. Pero me voy a quedar solo en esta.

******* Claro que la Juana de Arco está bien, pero me parece que no está tan bien, sobre todo pensando en las que quedaron debajo. Es un resultado de consenso de manual.

******** Sigue el disparate. 8½ está muy lejos de ser lo mejor de Fellini. Y en una lista en la que aún no aparecieron Bresson, Fassbinder o Cassavetes, esta irrupción felinesca se parece un poco al despropósito de 2001.

******** ¿Puesto 16 para Bresson? Creo que al menos hay 12 que no lo merecen. Y ni siquiera elijen al mejor Bresson: el Cura rural, el Condenado a muerte, el Carterista... (Podrían ser 3 de las 5 mejores películas de todos los tiempos).

********** Los 7 samurais, Persona y El espejo: una vez más, ni siquiera son las mejores de sus respectivos autores. Creo que estos votos revelan la inercia y la vagancia de los críticos a la hora de pensar el cine. Persona es una película indigna de Bergman. ¡Y todavía no aparecieron Fassbinder, Visconti y Rosellini!

*********** La aventura es una película influyente y estimable, pero Antonioni sigue estando sobrevalorado.

************ ¿El desprecio? Hmmm... Godard hizo estos últimos años tantas películas superiores a esta. Creo que El desprecio está en este lugar por el culo de Brigitte Bardot.

************* Rashomon, El padrino y Con ánimo de amar: nada que objetar: yo también las podría haber elegido. Pero como en esta lista no aparecieron Fassbinder, Cassavetes, Visconti, Rosellini, el Cura Rural, el Condenado a Muerte, El carterista, Notorious... ¡está todo mal! Hace poco Perrone me decía que Bresson está olvidado y yo le decía que no: tenía razón él.

(Lista completa acá)